Hong Kong director Wong Kar-Wai is one of a kind. Not many filmmakers working in the 1990s and early 2000s have left such an indelible impression on contemporary cinema. With much of his back catalogue recently remastered for the big screen, we couldn’t be more excited to be showing four of his masterpieces throughout February. In this blog, UPP Duty Manager and Projectionist Martina Bani explains what she loves about the films of Wong Kar-Wai by focussing on the mood, the music, and the magic of cinema created in his works.

We go to the movies not to attend a series of events but to feel a certain way. We are in the mood for a certain story. By allowing films to elicit moods in us, we engage in the experience of art. Wong Kar-wai masters the subtle art of evoking moods like no other. Consider Yumeji’s theme from In The Mood For Love (2000):

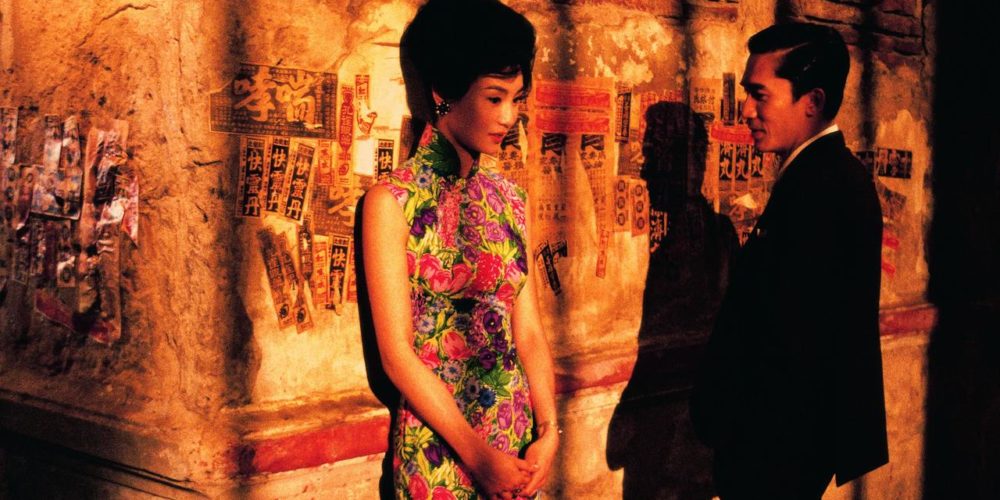

Two chords and I’m immediately transported back into the world of rainy Hong-Kong alleys, over-saturated wallpapers and 60s floral cheongsams. Let me be clear, it’s not just the case of a well-chosen soundtrack. Rather, Yumeji’s theme dictates the tempo of the entire film: in its slow-motion repetitions, it works as a connective thread. It delineates echoes and patterns between scenes punctuating the romantically alluring dance of the protagonists’ Chow Mo-wan (Tony Leung) and Su Li-Zhen (Maggie Cheung). The theme unravels their cadenced steps between reality and fantasy, amid which feelings start to “creep up”. Rhythmic and yearning touch, but no embracing climax: their steps never come to complete fruition, always ending up just missing each other. In other words, Yumeji’s theme embeds a whole soundscape: a ‘mood-verse’.

Moods are also liminal: they pervade the spaces in between, like spirals of cigarette smoke. Roaming between the longing for a vanished past and that for a future that was (but will never be) is a special form of existential liminality that reverberates across Kar-wai’s films. This is the place of smells that recollect entire eras, slippers that bring back love stories, or the indents on Angkor Wat’s columns evoking millennia of intrigues. Hong-Kong’s temporalities, either factual or in Kar-wai’s mind, have an expiry date. His films do not follow linear succession, making their protagonists’ connections ephemeral: never consummating one’s love means infinitely delaying its moment until nothing remains. Many find this recurrent trait of Kar-wai’s films upsetting. I don’t: love, as life, doesn’t need satisfying completion to have value or meaning. Meaning is here, in itself, by the sheer fact of happening. Or having happened. Or, being inhabited while it was happening. This is liberating: despite new worlds coming anew and demolishing what once was, despite traces of memories running away like tears, one might say that their meaning, their mood, is heightened and becomes sacred. It’s the secret power of memories: gathering intensity the more the present dissolves.

Yumeji’s rhythmics is also the soul of its film. A similar story applies to Kar-wai’s idiosyncratic slow-motion scenes across many of his works. He seems to want us to inhabit the moment, dwell and breathe in its texture. A stylistic fabric like this is noteworthy for two reasons: first, it makes his films celebrate a sort of human “being” rather than a human “doing”. We meditate through the scenes more than witnessing what happens in them. Secondly, it adds a new aesthetic possibility for film, as a medium, to communicate. What I mean by that is that the slow-motion scenes, the luxuriant visuals, or the entrancing score are not mere exercises in style but specifically designed elements in the service of the story.

But “story” is not even the right word here. They are in the service of the mood of the film, which includes the story, the costumes, the feelings and all the meanings in-between. By enhancing each other, they make the film’s universe, or moodverse, pregnant with meaning. Wong Kar-wai’s stylistic identity elevates us from happenings while penetrating them deeply. Meaning is constantly concealed and revealed in its concealing, which in turn comments on the nature of film as a form of art. Philosopher Stanley Cavell remarks that “It is as if an inherent concealment of significance, as much as its revelation, were part of the governing force of what we mean by film acting and film directing and film viewing”. Films like In The Mood For Love, Fallen Angels, Chungking Express and Happy Together operate across levels of significance that, on screen, make us inhabit and switch between whole planes of consciousness. This is what makes Wong Kar-wai’s art one of a kind.

Our World of Wong Kar-Wai season takes place between Sunday 30 January and Wednesday 23 February. The full list of titles and links to booking can be found here.