It would be fair to say that the Coen brothers made some of the best American films of the 90s and the early part of this Century. And it might also be fair to suggest that, since they stopped working together, it’s been slim pickings (Joel’s black and white version of Macbeth with Denzel Washington was impressive, but not so sure about Ethan’s recent “lesbian noirs” Drive-Away Dolls and the soon to be released Honey, Don’t!).

They hit the ground running way back in 1984 with the superb neo noir Blood Simple (which introduced us to the many talents of Frances McDormand, who went onto feature in a great many of the brothers’ movies, most notably Fargo, and to marry Joel). Blood Simple is a dark tale of infidelity and revenge, topped off by a brilliantly sleazy performance from M. Emmet Walsh as a private investigator. Its last shot is outrageous (Barry Sonnenfeld, who went onto direct, amongst others The Addams Family, Get Shorty and Men in Black, was the cinematographer) and the film was edited by Roderick Jaynes (which turned out to be a pseudonym for the directors).

This was followed by the hugely enjoyable road movie Raising Arizona, which starred Nic Cage (at the top of his game) and the fabulous Holly Hunter as a childless couple who attempt to steal a baby – with hilarious and surprisingly moving results.

The 1990s, however, saw the brothers really get into their stride, making a run of films which included gangster drama Miller’s Crossing (1990); apocalyptic dark comedy Barton Fink (1991); commercially disappointing but personal favourite The Hudsucker Proxy (1994) with Paul Newman; Oscar winning ice cold police drama Fargo (1996) and, in case you thought it couldn’t get any better, cult bowling crime comedy The Big Lebowski in 1998.

The Twentieth Century sees the brothers team up with “heart throb” George Clooney for the offbeat chain gang musical based on The Odyssey O Brother, Where art Thou? (2000) which is being screened this month as part of a much needed musical comedies season (the summer has, after all been rather dominated by horror films and, unsurprisingly there’s a lot more to come before Halloween); rather forgettable rom com Intolerable Cruelty (2003); paranoid conspiracy spy drama Burn After Reading (2008) and he’s back as a nice but dim actor in their penultimate film thus far Hail, Caesar! in 2016.

The early 2000s also gives us the very offbeat black and white hairdresser noir The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001); Oscar winning Cormac McCarthy adaptation No Country for Old Men (2007) which for many years was an A Level Film Studies set text; 2009’s incredibly good Jewish Rabbi head scratcher A Serious Man (another personal favourite) and their first really poor film, a mis-judged re-make of Alexander Mackendrick’s Ealing comedy The Ladykillers (2009), which starred Tom Hanks.

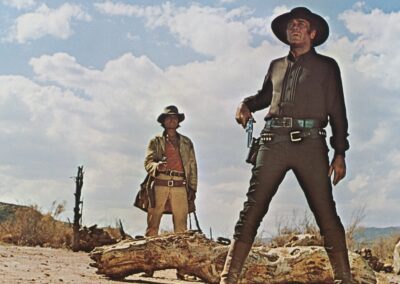

Their final films include the 2010 re-make of the western True Grit (which sees them team up once more with The Dude himself Jeff Bridges); 2013’s strangely moving, wintery, 60s set folk musician shaggy dog tale Inside Llewyn Davis, starring Oscar Isaac and Carey Mulligan (screened earlier this year to tie in with the release of the Timothy Chalamet Bob Dylan movie and which I thought had begun to age really well and is now a contender for my absolute favourite film in the Coen brothers’ canon); the afore mentioned (too many?) star-studded Hollywood satire Hail, Caesar! and, indicative of the times we live in, their final film as a team, another western for (horror of horrors) streaming platform Netflix The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (which contains no less than six separate stories).

You know when a director has hit paydirt when the suffix “- esque” is added to their name, for example Hitchcock-esque; Kubrick-esque and Tarantino-esque. And the Coens have entered this small group of revered film makers, with the term Coen-esque being used to describe any off-beat, hard to pin-down, narrator-driven, difficult to categorise, zany, pitch black take on genres (especially crime) either made by themselves (as in, “the film ends with a Coen-esque flourish”) or made by a film maker whose work appears to be indebted to the duo in some way (Darren Aronofsky’s forthcoming Caught Stealing might well be an example of the latter).

There was certainly a point early on in the brothers’ career when it looked like they could do no wrong and a new Coen brothers’ film was a hotly anticipated event.

The list of actors who have worked with them is an impressive one and includes, amongst others already mentioned (deep breath) regular collaborators (the always outstanding) John Goodman and John Turturro, Albert Finney, Gabriel Byrne, Judy Davis, William H. Macy Tim Robbins, Jenifer Jason Leigh, Steve Buscemi, Charles Durning, Billy Bob Thornton, Catherine Zeta Jones, Phillip Seymour Hoffman,Tommy Lee Jones, Javier Bardem, Josh Brolin, Brad Pitt, John Malkovich, Tilda Swinton, Michael Stuhlbarg, Matt Damon, Hailee Steinfeld, F. Murray Abraham, Adam Driver, Scarlett Johansson, Ralph Fiennes, Liam Neeson and Tom Waits.

Other collaborators who have added a great deal to the “Coen-esque” feel are composer Carter Burwell (who has scored almost all their films plus, amongst others, Todd Haynes’ Velvet Goldmine; Spike Jonze’s Being John Malkovich; the Twilight saga; Carol (another A Level Film Studies set text); as well as In Bruges, Three Billboards and The Banshees of Inisherin for Martin McDonagh.

And, in addition to the work of Barry Sonnenfeld, the Coens have also collaborated with genius cinematographer Roger Deakins on the majority of their films, along with Emmanuel Lubezi (Gravity, Birdman, The Revenant and Tree of Life, to name but four) and Bruno Delbonnel (best known for Amelie and, recently, Wes Anderson’s The Phonecian Scheme).

Because the Coen brothers almost always wrote, produced, edited and directed their movies, there is also a consistency of style even when the genres are very different. Andrew Sarris claimed that to be considered an “auteur” director, it was important to be technically accomplished, personal and to explore consistent themes. The Coens most certainly fit that description with their films often exploring outsider figures, the “evil” that men do, the American myth of the road and Hollywood itself. The writing is almost always absolutely on the nose (apparently they tend to write the parts with actors in mind) and the performances in Coen brother films are usually exemplary. They are definitely cineastes, although their films appear to be without overt influences from other film makers and their off-beat sense of humour is something that makes them a slightly acquired taste but may also account for the cult-following they have acquired.

As a teacher I used to think that the Coens would always be appreciated in the classroom. However, it might be fair to suggest that the sophistication and “cleverness” of Coen brothers’ films is increasingly alien to a number of pupils whom I teach. You have to do a bit of work to “get” the Coens; apply yourself and “tune in” to their leftfield wavelength. Whilst Fargo and No Country still “play well” in Film Studies lessons, I have noticed that some of their movies no longer go down quite so well and I was quite surprised to find that The Big Lebowski wasn’t enjoyed as much as I thought it would be, when I watched it with one of my classes a few years ago. The students found it difficult to “get over” the “90s-ness” of it and found its humour to be too cerebral.

O Brother, Where Art Thou? is a goofy, quotable take on Homer (it will be interesting to see how it holds up next to Christopher Nolan’s forthcoming take on the same story) with a lot of fun to be had. Its musical numbers by T Bone Burnett are both witty, authentic and memorable; Roger Deakins does his usual expert job bathing whole thing with gorgeous colours and fabulous framing; Clooney, Turturro, Tim Blake Nelson and a returning Holly Hunter are all outstanding and John Goodman’s performance is, as you’d anticipate, both eccentric and, at times, terrifying. Only the Coens could pull off the Klu Klux Klan sequences (much more subtle than Tarantino’s in Django Unchained) and the ending is another of the Coens’ best.

Now that it’s 25 years old, this is a film well worth catching on the big screen if you’ve never seen it or have only ever watched it on DVD or (gulp) via streaming. And even if you did see it when it first came out, 25 years is a long old time and given what follows in film this century, might leave you wondering at a time when Hollywood was turning out such unique and unpredictable films as these, which managed to both find an audience, Oscar voters and appeal to the critics.

O Coens, Where Art Thee? indeed. Let’s hope that we will see the two brothers reunite at some point in the future and make another film that demands to be seen at the cinema rather than on TV. The film world is a much smaller one without them.

Dr Andrew C Webber is a Film teacher and examiner with 40 years’ experience. He currently contributed to both the sadly defunct Cinema of the 70s and 80s magazines (available on Amazon); cassette gazette fanzine (available from cassette pirate on e-bay) and the Low Noise music podcast available on Spotify and Apple podcasts (about to begin its fourth season).