The famous Bonnie and Clyde tagline: “They’re young. They’re in love. They kill people.” could have easily been applied to Terrence Malick’s 1973 unforgettable debut Badlands which is, like every other movie released that year, now celebrating its 50th birthday.

In actual fact, the movie was shot in 1972 but Malick, only 30 but even then a perfectionist, took a full year or so to edit the footage, which had been shot by no less than three cinematographers (including novice Tak Fujimoto) with Robert Estrin (who had previously edited Michael Ritchie’s excellent political satire The Candidate starring Robert Redford in 1972).

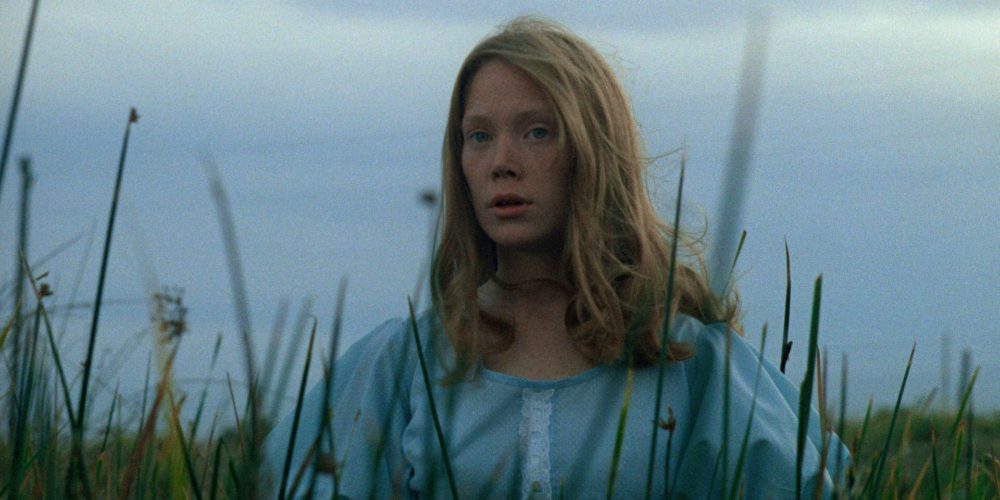

The film (loosely based on a true story) also featured relatively fresh talent in front of the camera. Sissy Spacek, who plays the naïve smalltown girl Holly and who would go on to find acclaim in Brian De Palma’s Stephen King adaptation Carrie in 1976, had only been seen on screen once before, in Michael Ritchie’s violent gangster movie Prime Cut. Martin Sheen (who would be electrifying in Coppola’s 1979 Apocalypse Now – even if he did suffer a heart attack and breakdown during its arduous filming) plays a former garbage collector and James Dean wannabe, Kit, who sweeps Holly off her feet, much to her father’s chagrin, before heading off on a killing spree in the Texas badlands. At this point in his career Sheen had only appeared in a few minor roles, including parts in Mike Nichols’ Catch 22 (1970) and George C Scott’s long-forgotten Rage (1972). Both performances by these relative newcomers are outstanding.

Joining them, as Holly’s cigarette chewin’ painter father, is cult actor Warren Oates, who was a character player of note and had appeared in many memorable roles on screen since the 1950s, including, of course, Norman Jewison’s Oscar winning In the Heat of the Night in 1967; Sam Peckinpah’s outstanding and controversial western The Wild Bunch in 1969 and both brilliant road movie Two Lane Blacktop and Peter Fonda’s undervalued Easy Rider follow up western The Hired Hand, in 1971.

The basic premise of Badlands (if you’ve never seen it) is best explained by the tagline the film actually used (both on the poster and in the trailer):

He was 25 years old. He combed his hair like James Dean. He was very fastidious. People who littered bothered him.

She was 15. She took music lessons and could twirl a baton. She wasn’t very popular at school. For a while they lived together in a treehouse.

In 1959, she watched while he killed a lot of people.

So, there you have it.

Badlands, like Bonnie and Clyde is a modern outlaw lovers on the run movie – a crime sub-genre Hollywood had been playing with since the 1930s, in, for example, Fritz Lang’s You Only Live Once (1937) with Henry Fonda and Sylvia Sidney; Raoul Walsh’s 1941 High Sierra (starring Humphrey Bogart and Ida Lupino) and Nicholas Ray’s 1948 They Live By Night (Farley Granger and Cathy O’Donnell). In fact, they would carry on playing with the concept for years to come, in, for example, Tony Scott’s 1993 True Romance (which contains several overt references to Badlands); Oliver Stone’s 1994 Natural Born Killers and even the recent Timothee Chalamet vehicle, teenage cannibal love story Bones and All (no wonder audiences stayed away).

In the 70s, of course, the genre was given a slightly new makeover by the short-lived popularity of the road movie – those (relatively low budget) films which followed in Easy Rider’s wake, and which gave film makers a chance to really explore parts of America that had hitherto been invisible on screen.

In the same year as Badlands, Steven Spielberg’s feature debut Sugarland Express charted Goldie Hawn and William Atherton’s attempts to get back their child by driving across America, hotly pursued by a cavalcade of cops and paparazzi; the road went literally “forever on” at the end of the Robert Blake starring motorcycle cop drama Elektra Glide in Blue (one of the great film titles of this or any other era); Ryan teamed up with daughter Tatum O’Neal to sell Bibles in Bogdanovich’s outstanding black and white comedy drama Paper Moon; Al Pacino teamed up with Gene Hackman to travel to Pittsburgh to open a car wash in Jerry Schatzberg’s little-seen Scarecrow (whose tagline read “John D Rockefeller. JP Morgan. Andrew Carnegie. Max and Lion.”); Walther Matthau went on the run from the bad guys in Don Siegel’s masterly heist thriller Charley Varick (better than Dirty Harry? Probably) and Nicholson and Otis Young accompanied Randy Quaid on his final journey to a naval prison in Hal Ashby’s freewheelin’ The Last Detail.

Yup, there was a helluva lot of travelling going on by oddball, eccentric, troubled and damaged losers in American cinema of the 70s – most of it, of course, on the road to nowhere, with many (but not all) of these films ending bleakly or abruptly – but hey, Nixon was still in Power, ‘Nam wasn’t really over yet and the peace and love movement had ground to a halt at Altamont, so what did you expect?

There are a great many reasons why you need to get along to see Badlands at the UPP this Valentine’s Day. Its amazing classical music soundtrack (featuring eclectic music by composers Erik Satie, Carl Orff and Saint-Saens – which shouldn’t work but does); the incredibly shot burning house scene; the moments where a pet catfish is thrown out and a dog shot by an angry father and Sissy Spacek’s off-beat, overly dramatic narration (a trick Malick pulled off, yet again, in his much delayed follow up, 1978’s Days of Heaven – surely a contender for one of the most ravishingly photographed films of this or any other decade?).

At the time, it wasn’t especially well received (the acclaimed New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael called it “so preconceived, there’s nothing left to respond to,”) and its cold, distanced, extremely detached attitude towards what is presented on screen is likely to be divisive. It’s certainly not a movie which tells you what to think all the time. Although it’s certainly a film which will make you think (there are so many ellipses – you have to!).

After his sophomore effort Days of Heaven, we had to wait until 1999 for Malick to make another movie when he finally returned with The Thin Red Line (in this reviewer’s opinion one of the greatest war films ever made – though it was overshadowed at the time by Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan).

Since 2000 he’s been pretty busy (I liked The New World but sort of gave up on him after Tree of Life). However, his most recent film, 2019’s A Hidden Place, which was given a brief release but has subsequently almost completely vanished, suggested a return to form, so maybe his forthcoming new film – the Biblical epic The Way of the Wind (Mark Rylance is Satan and Son of Saul’s Geza Rohig is Christ, apparently) might be his masterpiece?

Only time will tell.

Until then, take your partner by the hand, drag ‘em down to the UPP in February and enjoy a film which, almost against the odds, is swoonsome, haunting and, as is so often the case with Malick’s cinema: achingly beautiful – like all good anti-Romances should be.

Dr Andrew C Webber is a Film teacher and examiner with over 37 years’ experience. He currently contributes to both the Cinema of the 70s and 80s magazines (available on Amazon); cassette gazette fanzine (available from cassette pirate on e-bay) and the Low Noise music podcast available on Spotify and Apple podcasts.