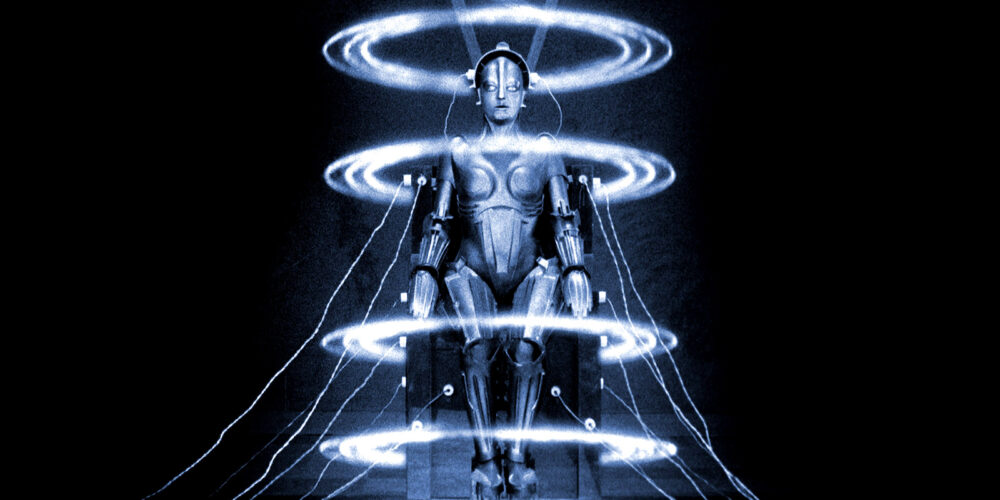

Whilst society has a habit of “catching up with” Science Fiction it rarely heeds the genre’s warnings. The forthcoming short season of films chosen to reflect the latest developments in Artificial Intelligence which have been dominating the news over recent months, which includes Kubrick’s brilliant 2001: A Space Odyssey (a film which should always be seen on the big screen at every available opportunity); a double bill of Blade Runners (Villeneuve’s “sequel” is likely to be divisive); The Iron Giant (arguably one of the greatest animated films of the last 30 years – see it with or without younger children) and “daddy of them all” Fritz Lang’s 1927 silent masterpiece Metropolis, is packed full of stories which ask audiences to think again about technology and how we use it. All of them suggest that an over-reliance upon computers and robots pose very real risks for us and several of them force us to confront that ageless Sci Fi theme: what if we managed to create beings who are actually superior to ourselves: would they dream of electric sheep and would we have the capacity to destroy something that shared our ability to love, remember and share with us the joys of sentience in all its glory?

GCSE English Literature students across the country still study Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’ – the novel from 1818 which deals with the dichotomy of playing God and creating a life “that does not want to be born” and remains thought-provoking and fascinating to young minds all these years later. In many ways, her novel set the template for the “hard” Science Fiction narratives which followed.

Most genres can be divided into the sub-categories of “hard” and “soft,” if you think about it: “soft” Sci Fi would include things like Star Wars and Buck Rogers or Flash Gordon. “Hard” Sci Fi, on the other hand, would have to include those novels and films with more complex, intelligent ideas, For example, cult classics 2001, Solaris and Blade Runner and a surprising number of solid American movies from the late 60s and 1970s, including Franklin J Schaffner’s Planet of the Apes; Joseph Sargent’s Colossus (a computer takes over the world, surprisingly); Robert Wise’s brilliant The Andromeda Strain (a pandemic is caused by an alien virus); Richard Fleischer’s Soylent Green (which dealt with over-population); Michael Crichton’s Westworld (watch out for the robot cowboys); Norman Jewison’s Rollerball (which explored our love of violent sport and corrosive celebrity) and Logan’s Run (in which you die when you reach 30). Fine films all, from Cinema’s second Golden Age.

Of course, Science Fiction films have always been warning us about something or other. During the Cold War there was a sense of paranoia in America about “Reds” taking over the world, which was clearly reflected in movies like Siegel’s stunning 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers (the Kaufman 1978 remake is also pretty good – using grim post-Watergate cynicism as a backdrop) and The Thing from Another World (1951). The Iron Giant brilliantly plays with this by being set in the 1950s and, yet casting a very modern eye on the period.

There were also a number of films which (rightly) told us to fear what the Bomb might do – low budget GIANT! ANTS! ATTACK! creature feature Them! (1954) being a good example. Jack Arnold’s The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) is another story reflecting contemporary fears about radiation and its effects – Richard Matheson’s outstanding novel, published the previous year, is definitely one of the great unsung literary examples of the genre – way ahead of its time in terms of its concerns with both sex (what literally happens as the protagonist, ahem, grows smaller?) and musings upon the afterlife.

We have also been warned about the future by children’s films like Pixar’s Wall-E and Disney’s Tron; John Wyndham’s brilliant environmental disaster story The Kraken Wakes (1953) has inspired a number of films dealing with the end of the world caused by climate change and probably every post-Apocalyptic film or TV show you can name – from Cormac McCarthy’s The Road to the Mad Max movies and from The Hunger Games through to The Last of Us has had “something to say” about what could happen if we carry on the way we are going.

It would also be fair to say that hybrid horror/Sci Fi films like Alien and Aliens and The Terminator with their attacks on corporate greed have definitely got in on the act, as well as a great many films about gender featuring robot women, including The Stepford Wives, Ex Machina and, earlier this year, the amusing M3GAN (you can see the original “robot woman” in action in Lang’s Metropolis and, of course, Blade Runner contains some unforgettable images of their destruction).

So, this unmissable UPP season of Sci Fi gems serves to remind us that we should certainly be careful with how we utilise science and future technologies. That we should hold companies involved in the manufacture of A.I. to task and always consider the ethical dimension of scientific progress.

We already live in a world where we are no longer training ourselves to remember things because our phones give us all the answers; students at school are avoiding writing essays by downloading ChatGPT; relationships and human interaction are dominated by social media and digital platforms; children’s whereabouts can be monitored 24/7 by tracking devices which will soon be inserted beneath the skin; we commute like robots to work each morning conversing on our screens; sexbots can be bought to provide those that want it with sexual stimulation; few people still want to own (or read?) physical copies of books and records and even movies because, well, everything they need is available to download. We rely on our apps to tell us if it’s raining, rather than look out the window; have family meals spent in silence watching TikTok, sharing memes and scrolling and, hey, lest we forget, the nuclear bomb’s still out there (as Chris Nolan’s forthcoming Oppenheimer reminds us).

Arguably, now, more than ever, we need our movies to do what they have always excelled at: challenge dominant attitudes; ask questions; consider possibilities and force us to confront uncomfortable truths.

Science Fiction has always been one of the most subversive of genres – long may it remain so. Watch the Skies!

Dr Andrew C Webber is a Film teacher and examiner with over 37 years’ experience. He currently contributes to both the Cinema of the 70s and 80s magazines (available on Amazon); cassette gazette fanzine (available from cassette pirate on e-bay) and the Low Noise music podcast available on Spotify and Apple podcasts.