The recent acclaim meted out to Hauschka (AKA Volker Bertelmann) for his Academy Award winning, incongruous but effectively doomy soundtrack to Edward Berger’s Netflix funded All Quiet on the Western Front in 2022, would suggest that there’s still much to be said for three heavy synthesised chords and the truth (even if the sonorous notes were played on a century old harmonium belonging to his grandmother).

Of course there are many examples of films, going back to the late 60s, which also took advantage of the exciting, new electronic ways of making popular music which were developing at the time. Apparently, David Lean’s 1965 epic Dr Zhivago is on record as one of the first fully synthetic scores – although I might have put my money on the Theremin work done for science fiction classics Christian Nyby’s The Thing from Another World and Robert Wise’s The Day the Earth Stood Still. Influential composer Miklos Rosa had also been an early exponent of that highly unusual sounding instrument – using it to great effect on the 1940s films Spellbound for Alfred Hitchcock and Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend, for example.

However, as the 1970s surged ahead (arguably cinema’s greatest decade) more and more big (and small) movies came replete with what we might today call, a synth-heavy soundtrack – notable examples being Wendy (then Walter) Carlos’ work on Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange; the use of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells in The Exorcist in 1973; the haunting music for John Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 and, particularly, Halloween (written and performed by the director himself); the outstanding sonic work done by his father Carmine (with sound designer Walter Murch) to enhance the whirring helicopters on Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now and William Friedkin’s decision to use “Krautrockers” Tangerine Dream to write and perform the music for his flop Sorcerer (which is now widely considered, and probably is, his masterpiece).

The point here is that cinema has always been an audio-visual medium. Even silent films came replete with live or recorded music and there is no denying that a great many “golden age” directors clearly understood they were dealing with what the audience hears as well as what it sees – and that’s often what made them great. Like Welles before him, Hitchcock, for instance, teamed up with genius composer Bernard Hermann (another early dabbler in electronic instrumentation on The Birds in 1963) and made film after film where sound was everything (Vertigo, Psycho, Marnie, for example). Martin Scorsese and Brian De Palma certainly realised this when they both provided the ageing composer with career resuscitating jobs on Taxi Driver and Obsession (both 1976).

And who can forget how Leone totally understood that Ennio Morricone’s reshaping of the western soundscape could be an integral part of his vision (reaching its peak on both Once Upon a Time in the West and the forever devastating Gheorge Zamfir panpipes of Once Upon a Time in America)?

In the 70s, Horror films were unsurprisingly leading the pack when it came to innovative soundtracks and, after the already mentioned The Exorcist, you could experience Jerry Goldsmith’s Academy Award winning, dreadful sounds during The Omen, which featured mystic chanting that appeared to be calling us from Hell itself whilst, in space, no one could hear you scream because you were already unnerved, beyond belief, by his equally eerie 1979 score for Alien. Cult Italian giallo film maker Dario Argento was quick to enlist the oddball Goth rock band Goblin to make devilish sounds for, amongst others, his terrifying Suspiria in 1977 (George A Romero would “borrow” the band a few years later for Dawn of the Dead) and David Cronenberg’s relationship with Harold Shore also resulted in many an icy moment, in 1983’s Videodrome, for example. All these horror movies fully understood that it was as possible to terrify audiences with sounds as it was to shock them with images (arguably, sounds were even more disturbing).

And that’s without forgetting that these newly synthesised soundtracks were also playing significant roles elsewhere – German band Popol Vuh’s enormous contribution to Herzog’s historical epic Aguirre: Wrath of God; Francis (Sky) Monkman’s funky soundtrack for the seminal British gangster film The Long Good Friday and John William’s memorable work on Close Encounters, for example.

By the 1980s several new musicians/producers, who had proved themselves to be dab hands when it came to twiddling buttons and programming oscillators for pop performers were arriving on the movie scene and it would be fair to say that in the decade which followed, the sound of cinema went through a profound change and for that we should be grateful to, amongst others, Brad Fiedel for The Terminator (he’d played keyboards with soft rockers Hall and Oates); disco king Giorgio (I Feel Love) Moroder for Cat People (Bowie’s best theme tune?) and Scarface (Pacino’s hammiest performance?); Harold Faltermeyer, for the hit-tastic Axel F from Beverly Hills Cop and Fletch; Roxy Music’s Professor Brian Eno, who had joined in the fun by composing the music for the disastrous David Lynch version of Dune in 1984 and, uh, Rick Wakeman for Ken Russell’s Crimes of Passion.

In addition, we should not forget the work of at least three musicians who are sadly no longer with us and who seriously reshaped the way we thought about film soundtracks at the time – Vangelis (previously of Greek rock super group Aphrodite’s Child – which also featured the hirsute singer and “love god” Demis Roussos); Ryuichi Sakamoto (of Japan’s Yellow Magic Orchestra) and Angelo Badalamenti (who’d never been in a band, to my knowledge) – all three of them contributing to some of the most memorable films of the 80s: Vangelis winning an Academy Award for Hugh Hudson’s Chariots of Fire in 1981 and subsequently working on Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982); Sakamoto writing perhaps the greatest of 80s soundtracks, Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence for Nagisa Oshima in 1983 (a film he also starred in, alongside David Bowie) plus the Oscar winning score for Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1987 The Last Emperor (co-written with Talking Heads’ David Byrne). Whilst Badalamenti continually collaborated with David Lynch on a string of great movies including Blue Velvet (1986), Wild at Heart (1990), Lost Highway (1997) and personal favourite The Straight Story (1999) as well as, of course, the groundbreaking TV series Twin Peaks, arguably the greatest American TV show ever – or at least until The Sopranos came along.

Lest we forget, Vangelis also worked on Costa Gavras’ Academy Award winning Missing (1982), Roger Donaldson’s flop remake of The Bounty (1984) and (with Scott again) on the Christopher Columbus epic 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992) and Sakamoto went on to score, amongst others, The Sheltering Sky (1990) and Little Buddha (1994) for Bertolucci; De Palma’s Snake Eyes (1998) and 2002’s little seen Femme Fatale plus Inarritu’s The Revenant (2015). Meanwhile, Badalamenti collaborated with auteur directors Paul Schrader on The Comfort of Strangers (1990), Autofocus (2002) and his ill-fated Exorcist prequel Dominion (2005); Jean-Pierre (Amelie) Jeunet’s The City of Lost Children (1995) and A Very Long Engagement (2004) and, bizarrely, Malcolm Venville’s best-forgotten Ray Winstone-starring British thriller 44 Inch Chest (2009).

However, when you think about it, is there a finer 80s opening than that Vangelis-enhanced tracking shot through a futuristic, heavily polluted, rainy, night-time LA in 2019, which begins Scott’s still impressively dystopian Blade Runner? And who would have thought that, after appearing to be completely burnt out in 1979’s Apocalypse Now, Dennis Hopper would make a comeback quite as unhinged as his performance in 1986 as the gas guzzlin’ gangster Frank, in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet? Or, indeed, that Lynch himself would ever make another good movie, after the drubbing he rightfully received for the afore-mentioned mis-firing 1984 version of Frank Herbert’s Dune? More importantly, who’d have thought the whole thing would sound so, well, unbelievably weird?

And is there a greater freeze frame ending from the decade than the one which wraps up Oshima’s Mr Lawrence? Perhaps – Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America certainly gives it a run for its money, but there’s a big difference. Here we are pondering forgiveness, war, retribution, punishment, cultural difference, ageing, friendship, loss, the past. There we are simply wondering if it’s all been a dream (not quite, but you know what I mean)? As much as I marvel at the audacity of Leone’s conclusion to one of the most underrated movies of the period, in Mr Lawrence, it’s just a perfect coda to what has gone before, superbly segueing into a blast of Sakamoto’s main theme, which still brings this reviewer to tears on every listen (especially when accompanied by David Sylvian’s silky voice on the beautiful, stripped down version of the song, entitled Forbidden Colours, which appears as a bonus on his stunning Sakamoto produced 1987 Secrets of the Beehive album).

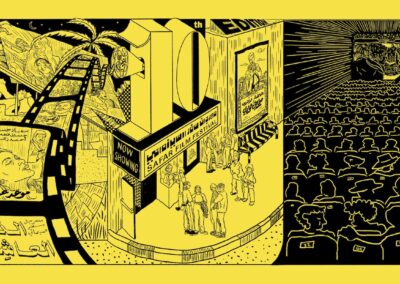

It is the work of these three composers that the UPP is showcasing over coming months and, if, like me, you are a lover of great music and great films, then what better place to get the full effect than on the big screen. Yes, you could download the soundtrack; yes, you could upload the film, but surely, by now, we all realise that the best way to “experience” a movie as it was intended, is at the cinema – that great institution, seriously needing our support in ever darkening times: a place where we watch with intent; listen carefully and, sometimes, emerge from the darkness with lives altered….always, ever so slightly.

And often, a great deal.

Dr Andrew C Webber is a Film teacher and examiner with over 37 years’ experience. He currently contributes to both the Cinema of the 70s and 80s magazines (available on Amazon); cassette gazette fanzine (available from cassette pirate on e-bay) and the Low Noise music podcast available on Spotify and Apple podcasts.