It might surprise you to learn that, contrary to popular belief, the western genre didn’t fall into abeyance in the 1970s, following the successes of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, True Grit, The Wild Bunch and the films of Sergio Leone in the 1960s. Far from it. It’s certainly fair to say, however, that during the 1970s, production of westerns decreased.

Wikepedia helpfully provides comprehensive lists of films made in different genres by decade and the list of 70s westerns it throws up makes for an interesting read. In 1970, for example, 75 westerns were made; in 1971 and ’72 there were 50; 25 were made in ’73 but, by 1979, that number had decreased to 16. And, although it has been unfairly maligned (I think it’s a masterpiece), Michael Cimino’s 1980’s Heaven’s Gate does effectively kill off the genre and the studio which made it (costing $44 million to make and grossing a mere $3.5 million) although one could also argue that Mel Brooks’ 1974 Blazing Saddles spoof was actually a bigger nail in the genre’s coffin – making it impossible for audiences to take some genre tropes seriously thereafter.

However, that list of westerns made in the early 1970s includes some real corkers – Peckinpah’s The Ballad of Cable Hogue, Penn’s Little Big Man (based on Thomas Berger’s brilliant novel), Silverstein’s A Man Called Horse, Fraker’s Monte Walsh, Nelson’s Soldier Blue and Siegel’s Two Mules for Sister Sara came out in 1970. 1971 brought us Siegel’s The Beguiled (remade in 2017 by Sofia Coppola), Perry’s very revisionist Doc, Leone’s Fistful of Dynamite, Kennedy’s Hannie Caulder, Fonda’s The Hired Hand (whilst he wasn’t officially a “movie brat,” it’s interesting to note that Peter [Easy Rider] Fonda is one of the few “New Hollywood” directors to try his hand at making a cowboy film – Spielberg, De Palma, Scorsese, Milius and Coppola never gave it a shot – unsurprisingly, this was hated at the time of its release but is well worth seeking out), Medford’s The Hunting Party, Winner’s Lawman, Altman’s (massively derided but incomparably beautiful) McCabe and Mrs Miller, Sherin’s Valdez is Coming and Blake Edwards’ undervalued Wild Rovers. Whilst, in 1972, we could see Bonnie and Clyde scriptwriter Robert Benton’s directorial debut Bad Company, Winner’s Chato’s Land, Rydell’s The Cowboys, Richards’ Culpepper Cattle Company, Kaufman’s Great Northfield Minnesota Raid (effectively remade in 1980 by Walter Hill as The Long Riders – a personal favourite), Pollack’s Jeremiah Johnson, Huston’s Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (scripted by John Milius, who at least tried) and Aldrich’s Ulzana’s Raid.

If these films have anything in common (other than the fact that many of them are extremely good), it’s that these westerns were made in the aftermath of Vietnam, in a climate of post-Watergate paranoia, at a time when “peace and love, man,” appeared to be dying in a dusty gulch somewhere with a bullet in its gut and the horror genre was literally tearing apart the moral fabric of American society in ever-increasingly brutal ways. In fact, I’d even go so far as to suggest that the 1970s turned out to be one of the greatest of decades for the “Oater” (as they were sometimes derivatively labelled) and, just as Film Noir saw itself rebranded as “neo-Noir” in the same era, perhaps we should now label all the westerns made then as “neo-westerns?”

“Neo-westerns” (with the exception of Hannie Caulder) are films about men: death’s never very far away and often its heroes are men out of time, seeking redemption in a changing world they no longer feel a part of.

But, as has been noted in my previous blogs about 70s cinema, the representation of casual and sexual violence against women is certainly a real problem when it comes to a lot of films from the decade – especially (but not exclusively westerns). It’s at the heart of Michael Winner’s right wing vigilante crime drama Death Wish; Peckinpah’s controversial Straw Dogs (“The knock at the door meant the birth of a man and the death of seven others”); Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (which was sold on the UK poster as “being the adventures of a young man whose principal interests are rape, ultra-violence and Beethoven”); Lamont Johnson’s Lipstick and Richard Brooks’ Looking for Mr Goodbar, for instance but does also rear its ugly head in a dispiriting (and disproportionate) number of the new “brutalist” neo-westerns of the decade, including Alf Kjellin’s The McMasters (“After the wedding they were given a real fine reception”); the Gene Hackman and Candice Bergen starring The Hunting Party (“You’re invited to a party… We’ll play the deadliest game of all… Hunting. 26 Men and 1 Woman!”); William Holden’s The Revengers and both Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter and The Outlaw Josey Wales, as well as a significant number of films dealing with native Americans, like Ralph Nelson’s still shocking Soldier Blue; Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man; Winner’s Chato’s Land and Aldrich’s Ulzana’s Raid. Somewhat ironically, the only reason Raquel Welch learns to handle a pistol in Hannie Caulder is also to revenge herself on the men who gang raped her at the beginning of the film.

So, the issue of violence against women may well make a number of neo-westerns unpalatable for modern viewers. However, if you can get beyond this, it’s worth reminding yourself that, in many ways, what differs the neo-western from its earlier incarnations, is the fact that the neo western IS an old man’s genre, although a few earlier westerns had touched on the theme of ageing, for example the “classics” The Searchers and High Noon. “Traditional” westerns also often dealt with ideas about the land, civilisation, community and revenge.

In the 1960s George Roy Hill had “sexed” things up by casting young heartthrobs Newman and Redford as Butch and Sundance and Eastwood was at the time in the prime of youth, but, as Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch proved – the genre was somehow richer when it used grizzled, older actors, sometimes past their prime to play those lost souls around whom the genre revolved. “Four men who came too late and stayed too long,” was The Wild Bunch tagline. And think about those wrinkles on the performers’ faces in Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West. The film just wouldn’t work with younger, fresh, clean-cut actors – we need to feel that these characters are lived in. Every frown-line and scar, whisker and grey hair suggest lives lived, battles lost and won. These are men long on memories and regrets but short on futures. And they know it. Amongst their many regrets are often the ways they have treated women and their desire for redemption. Some of them even try to make things better by learning to atone. To love.

It’s also worth remembering that in the 1970s, whilst there were a great many new guns on the block, in the form of hip young male actors like De Niro, Jack Nicholson, Al Pacino and James Caan; the stars of the studio days were still available for work and actors including Charlton Heston, Gregory Peck, Burt Lancaster (whose trio of 70s westerns Lawman, Valdez and Ulzana’s Raid are all excellent), Lee Marvin, Henry Fonda, William Holden and, of course, The Duke himself (John Wayne, ending his career in 1976 with the masterly The Shootist) still knew how to ride, had fan bases and could be credible in the roles of older cowboys with their best days behind them. They also brought with them the legacy of their earlier work – so that audiences could somehow see the back story of the characters they played, through the prism of their previous films (The Shootist begins with a montage of clips from Wayne’s formative westerns; Eastwood plays on his back catalogue in Unforgiven and it’s hard, even these days, to separate the Kevin Costner of Wyatt Earp, Open Range and, of course, Dances with Wolves when you watch him in Horizon – incidentally, my favourite film of 2024 – regardless of its critical mauling – plus ca change, and all that).

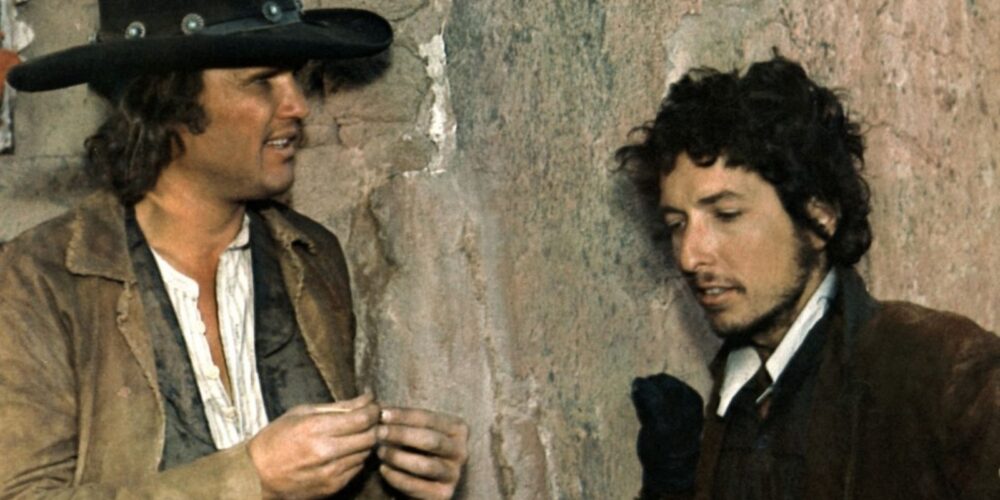

Which brings me to Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid from 1973, which you can see at the UPP in January, one of the few westerns which brings a tear to my eye every time I see it (possibly even more so now, following the recent death of its star Kris Kristofferson).

You can read elsewhere about the chaos of the film’s production – how it was effectively buried and butchered by the studio and savaged by the critics at the time; how little love there was for Bob Dylan’s original soundtrack and how Peckinpah’s career never really recovered from the mess and he never shot another western afterwards (although that didn’t stop him making 1974’s Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, 76’s The Killer Elite, 77’s Cross of Iron [his only war movie – and a brilliant one too], 78’s Convoy and his 1983 swansong The Osterman Weekend).

This is a classic “old man” movie (in spite of Dylan’s youthful appearance). The main star is James Coburn, a classic “swinging 60s” star, now past his prime. Other actors who appear in the movie have a long history of working in the western genre (Jason Robards, Chill Wills, RG Armstrong, Matt Clark, Jack Elam, Slim Pickens and Katy Jurado, amongst others) and, as well as the staggeringly good The Wild Bunch, Peckinpah had also made The Deadly Companions, Ride the High Country, Major Dundee and the afore mentioned Cable Hogue. Here was a director who lived and breathed the western.

And Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid effectively kisses the genre goodbye. A film about friendship, the past, time passing. Things concluding.

It was a film which appeared out of time in 1973 – the times were indeed ’a changin’: Jaws is round the corner; Taxi Driver and Star Wars beckoning; Joe Strummer of The Clash is about to tell us “No Elvis, Beatles, Rolling Stones in 1977.” And certainly no westerns. It is to my eternal shame, therefore, that in September 1976 I chose to see Alan Parker’s Bugsy Malone at the Odeon in Rochester as opposed to Don Siegel’s The Shootist. To be fair, I was only 12 years old but, to choose Alan Parker’s musical over The Duke’s swansong is something I will always look back on with a sense of regret. I cannot see myself ever returning to Bugsy.

I do, however, increasingly see myself as Pat as I grow old (wearing my trousers rolled). Knocking on Heaven’s door, going down in a hail of slo mo bullets (in a scene mercifully reinstated into the beginning of the film after Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid’s disastrous reception, over 50 years ago) and regretting so many choices made.

“Mom, put my guns in the ground, I can’t shoot them, anymore…that long black cloud is coming down…”

Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. Real cinema (and Sweet Dreams) are made of this. Do not miss.

Dr Andrew C Webber is a Film teacher and examiner with 39 years’ experience. He currently contributes to both the Cinema of the 70s and 80s magazines (available on Amazon); cassette gazette fanzine (available from cassette pirate on e-bay) and the Low Noise music podcast available on Spotify and Apple podcasts.