Directed by a drunken perfectionist, American born Scott, Alexander Mackendrick, who had previously made a number of much loved Ealing comedies (including The Man in the White Suit and The Ladykillers) The Sweet Smell of Success from 1957, which stars Burt Lancaster and Tony Curtis at the top of their game, feels like one of the great “New York” movies and you can see it on the big screen at the UPP in February, when it is playing as part of the Manhattan Melodies movies season.

The story of the troubled (and costly) making of this film is a fascinating one (although it’s worth remembering that the first film to be shot entirely on location was Jules Dassin’s The Naked City in 1948). The Elmer Bernstein (and Chico Hamilton Quartet) jazzy score is very much part of the film’s appeal; its literate script by acclaimed playwright Clifford Odets and Ernest Lehman (who would follow this with Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, West Side Story, The Sound of Music and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? amongst many others) is a master class in cynicism and the fact that the film was met with indifference by the public and critics when first released is just another example of how, very often, “great” films are initially misunderstood and their genius sometimes takes decades, before it is finally celebrated (other examples include Murnau’s 1927 Sunrise, Welles’ Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons; Cukor’s A Star is Born, Hitchcock’s Vertigo; Altman’s McCabe and Mrs Miller, Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid [which I wrote about last month], Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate and Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America, to name but a few personal favourites).

In this article, however, I want to focus on the contribution of the cinematographer James Wong Howe, whose life as a Chinese born “outsider” in Hollywood is both fascinating and shocking and whose career and influence is impressive.

In a career which included shooting over 120 movies from 1923 until 1975, Wong was nominated for 10 Academy awards, winning twice (for The Rose Tattoo in 1955, a Tennessee Williams play, turned into a Burt Lancaster movie, directed by Daniel Mann and Martin Ritt’s neo-western Hud, which starred Paul Newman, in 1963).

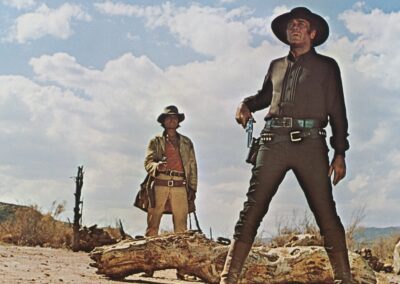

His most well known films include the James Cagney musical Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942); Abraham Polonsky’s powerful and bleak boxing drama Body and Soul (1947); the Burt Lancaster starring recovering alcoholic melodrama Come Back, Little Sheba (1952); John Frankenheimer’s terrifying Seconds (1966) with Rock Hudson; Martin Ritt’s “Paul Newman IS a Native American western” Hombre (1967) and his final film, the musical sequel Funny Lady (1975) which, of course, starred Barbra Streisand.

Noted for his ability to work beautifully with shadows (long before Gordon “The Godfather” Willis, who also became renowned for his propensity for darkness) and, apparently, the original “deep focus” king (using the technique years before it was championed by Orson Welles and Greg Toland in Citizen Kane), Wong Howe, who was born in the city of Taishan in 1899 but moved to America at the age of five, when his father went there to work on the railways, originally intended to become a boxer.

His family ran a general store in Oregon where, legend has it, Wong Howe encountered his first camera – but his entry into Hollywood was largely via luck (a chance encounter with Mack Senett; the patronage of none other than Cecil B DeMille) though, initially, like so many other “creatives,” he found it hard to adapt to the arrival of the talkies in the late 1920s, taking on extra work as stills’ photographer to make ends meet.

His preference for black and white over colour is well documented and his attention to detail occasionally caused conflict with both directors and actors – giving him the reputation of someone “hard to work with” and a bit of a maverick (my kind of guy). However, in this case, it’s not his illustrious career I want to reassess (just watch the Grand Central Train Station opening sequences in Seconds if you want proof of his genius, or, of course, any shot in his Weegee inspired camera set ups in The Sweet Smell of Success). It’s his personal life and what this tells us about the “outsider” experience in America in the early part of the Twentieth Century that I want to focus on.

Wong Howe met American journalist Sanora Babb at some point before WW2 and, in 1937, they were married in Paris. However, upon returning to the “good Ol’ US of A,” the couple discovered that, due to laws banning interracial marriage which existed in California (and were not repealed until 1948) the studios would not recognise the Wong Howes’ marriage. There was a “morals” clause buried somewhere in his contract which meant that he was prohibited from publically admitting to being married to a white woman (and thus committing the “felony” of miscegenation) and the couple were therefore not allowed to cohabit – they ended up with separate apartments in the same building, would you believe?

Dating back to the early 1800s, these racist laws were typically used to prevent black and white couples from “fornication” and “adultery” but were also used in cases of Native American and Asian American marriages.

Whilst California banned the laws in 1948, when the Wong Howes were finally able to find a Judge who would perform the marriage in America (and who reportedly said “She looks old enough. If she wants to marry a chink, that’s her business,”) it was not until 2000 that these laws were finally repealed in all states (the last bastion of anti- miscegenation was, unsurprisingly Alabama).

Both Babb and Wong Howe went on to espouse strong left wing views and both fell foul of the House Un-American Activities Committee, overseen by the notorious “Anti Pinko” Senator Joe McCarthy during the 1950s. Howe also became the first minority cinematographer admitted to the ASC (American Society of Cinematographers) where he mentored, amongst others, John Alonzo, who went on to shoot Polanski’s neo-noir masterpiece Chinatown, in 1974.

Howe passed away in 1976, aged 76 but Babb (who retained her maiden name) lived on, publishing and writing, well into her 80s, until 2005, when she finally died at the ripe old age of 98.

Her seminal Dustbowl/Great Depression novel Whose Names are Unknown, written at some point earlier in her career but shelved by the author, was finally published to great acclaim in 2004 – one year before her death. Comparisons to Steinbeck’s 1939 novel The Grapes of Wrath were somewhat inevitable – especially as it was subsequently pointed out that her notes had actually been used as the basis for his book.

Steinbeck was awarded a Nobel prize, in 1962, largely due to the impact that his novel had upon readers worldwide. Cynics might argue that this is yet another case of “Dorothy and William Wordsworth syndrome.”

James Wong Howe and his wife Sanora Babb. Both genuine American pioneers.

Dr Andrew C Webber is a Film teacher and examiner with 39 years’ experience. He currently contributes to both the Cinema of the 70s and 80s magazines (available on Amazon); cassette gazette fanzine (available from cassette pirate on e-bay) and the Low Noise music podcast available on Spotify and Apple podcasts.