I wrote in a recent blog that, in spite of directing both West Side Story and The Sound of Music plus the supernatural chiller The Haunting (recently screened at the UPP for Halloween), Robert Wise is not a name which tends to come up when thinking about Hollywood’s greatest directors.

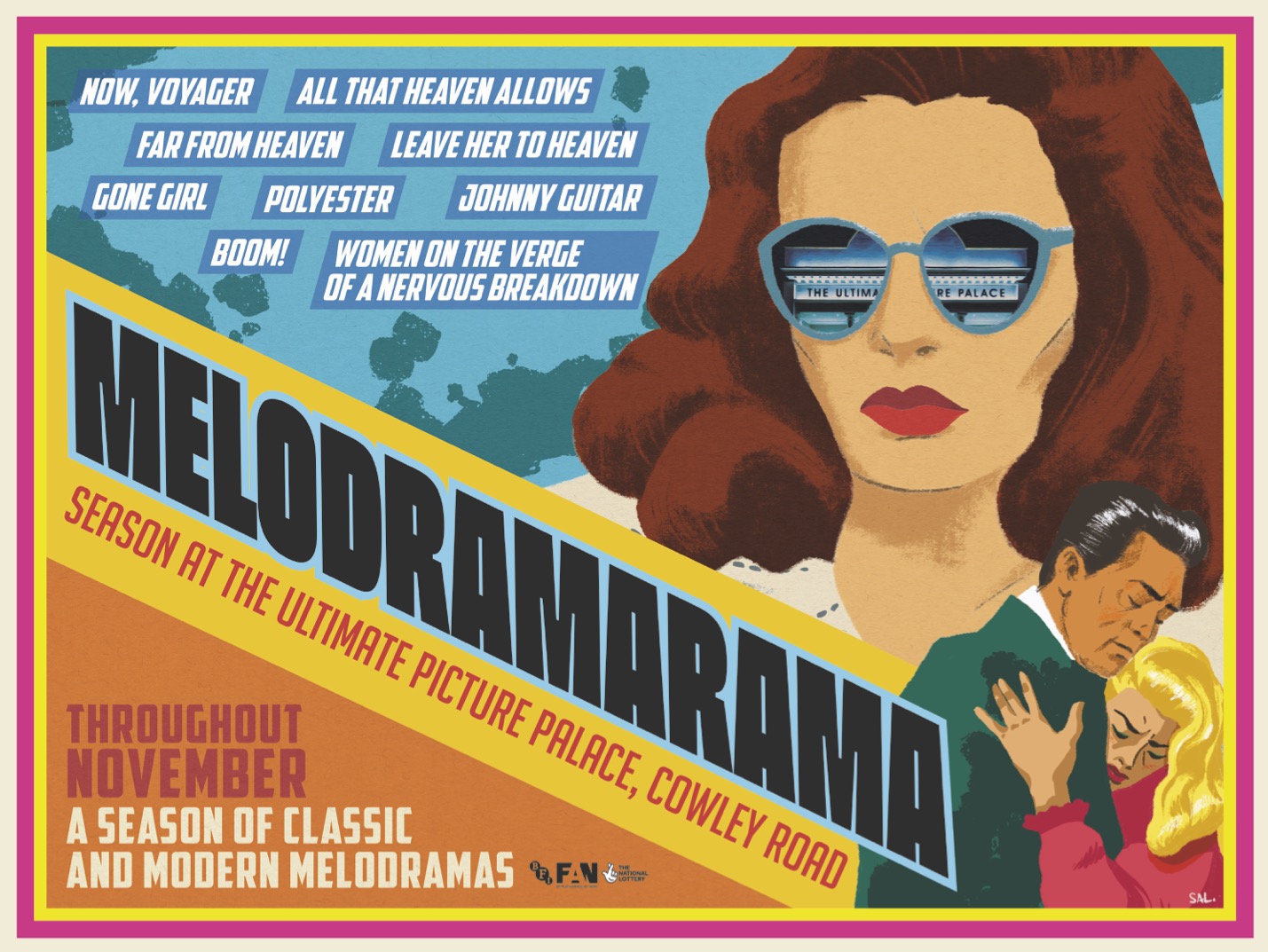

On the other hand, whilst his name may not exactly trip off the tongue, Nicholas Ray often does and yet his is not a name that you might be familiar with – in spite of the fact that he directed over twenty movies, including the brilliant film noir In a Lonely Place (1950) with Humphrey Bogart; James Dean’s iconic Rebel Without a Cause (1955); the little known but powerful addiction drama Bigger Than Life (with James Mason, 1956) and 1955’s very odd western melodrama Johnny Guitar (which used to be an A Level Film set text and is playing at the UPP this November, as part of its BFI supported Melodramarama season).

It’s interesting to recall that, when I was at University in the early 1980s (amongst the very first groups of students to ever study for a Film degree in this country) it was not, perhaps surprisingly, Hitchcock whom we analysed but, under the ever watchful eye of lecturerVictor Perkins, it was Ray who held our undivided attention. The first film I ever wrote a sequence analysis of, was about a barroom scene from In a Lonely Place and I’m fairly sure that we did end of year exams on the 1952 Robert Mitchum rodeo drama The Lusty Men.

Whilst it would be fair to say that Ray’s films appeared to be fairly solid 1950s products, it’s pretty unlikely that we would have gone as far as Jean-Luc Godard, who famously declared that “the cinema is Nicholas Ray.” After all, we’d just lived through Hollywood’s second Golden Age and had been brought up on a diet of Scorsese, De Palma, Coppola, Kubrick, Malick, Pakula, Altman, Lumet, Romero, Cronenberg. The old order had crumbled, long live the new wave. These film makers made adult films with a savage edge; films directed by film makers who, themselves, were lovers of the movies. They were edgy, risk taking, starred cool, new actors like Pacino, De Niro, Hoffman, Nicholson, Streep and those former studio directors and actors, who were still “holding on” to their careers during that period – John Houston, Burt Lancaster, George Cukor, Elia Kazan, Kirk Douglas, John Wayne, Elizabeth Taylor etc. all appeared tired and, well, a bit past it, when compared to the explosion of new talent which was erupting all around them, making them appear increasingly irrelevant (regular readers will know how embarrassing, with the benefit of hindsight, it is to have to admit that, instead of seeing John Wayne’s brilliant swansong The Shootist at the cinema in 1976, I chose to see Bugsy Malone).

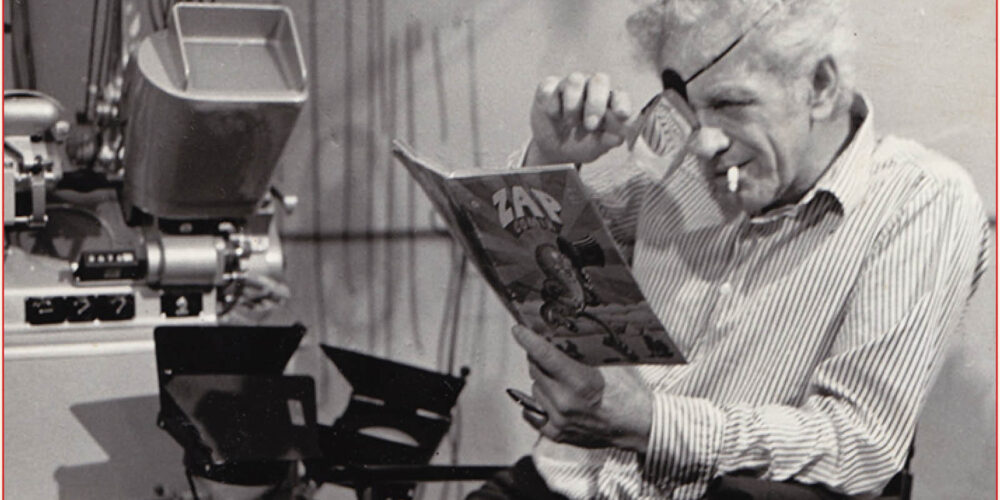

Ray was certainly one of those directors who had most definitely “fallen by the wayside” in the 1970s – struggling to get projects “off the ground;” reduced to making “experimental” cinema and dodgy softcore (1974’s Wet Dreams); and persona non-grata in Hollywood after his last big budget epic 55 Days at Peking (1963), which had starred Charlton Heston, Ava Gardner and David Niven, ended up costing over $10 million and had been a disastrous shoot (no one liked the script, which wasn’t finished when filming began; the cast constantly fell out with each other; everything went over-budget; Gardner was drinking and Ray eventually suffered a heart attack). No one had turned up to see it; it was critically mauled and behind the scenes, Ray had unsuccessfully struggled to get his name taken off the credits).

But the more you look into Ray’s personal life, the more you realise what a despicable person he probably was. He was a philandering drunkard, a heavy drug user, an adulterer, a violent partner, a man potentially torn up by homosexual desire in a heterosexual world; a “groomer” and someone capable of acting abusively to those he became close to. There are probably all sorts of psychological reasons for his behaviour and attitudes, buried in childhood trauma (there almost always are when people are this out of control) but it’s still hard to have much sympathy for him during the latter part of his career as he appeared to beg, borrow and steal to try (in vain) to get his career back on track – failing miserably and eventually dying, aged 67 from a mixture of lung cancer, brain tumour and finally heart attack in 1979, after years of poor health, brought about, in part by his wild lifestyle. We reap what we sow, indeed.

By modern standards, Ray would be “cancelled” and the fact that his name is not widely known, may, to some extent, be down to the fact that his early work has been overshadowed by a private life which included having “inappropriate” affairs with much younger women (most notably Natalie Wood, whilst they were making Rebel Without a Cause – she was 16, he was 43); apparently discovering his wife at the time (the brilliant but troubled Oscar winning actress Gloria Grahame) in bed with their 13 year old step son (who she eventually ended up marrying many years later, after she and Ray had inevitably divorced) and embroiling himself in a desperately clingy homosexual relationship with author Gavin Lambert, whilst simultaneously having flings with, amongst others Judy Holliday, Marilyn Monroe, Joan Crawford and Shelley Winters. The mind boggles.

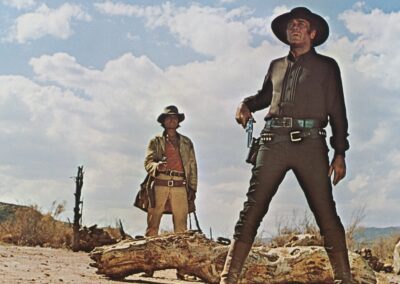

It has been suggested that Bigger Than Life, a film much admired by, amongst others, Martin Scorsese, is his most personal and autobiographical work but those who consider him to be one of the great auteurs often cite his recurring themes of masculinity in crisis, outsider figures and concern with social issues. He has been acclaimed for his use of colour (Johnny Guitar is shot [by Harry Stradling] in glorious Technicolor) and for that fact that he was adept at working across very different genres – although it is probably crime films where he really excelled (his 1948 debut They Live by Night turning out to have a very big influence upon the genre – it even ended up being re-made by Robert Altman, another admirer, as Thieves Like Us in 1974).

We will shortly see what the Nomadland Oscar winning director Chloe Zhao has made of Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell’s novel about Shakespeare’s life at the time of writing his masterpiece Hamlet. It should be an assured and interesting look at the artist and the process of writing a play, which may reflect and have been shaped by the author’s private life (in this instance, the unendurable loss of a child and the ramifications of that upon a marriage). But I think we have to be careful when it comes to linking works of art too closely with the lives or personalities of their creators.

From what I read, Ray certainly comes across as an unpleasant and manipulative man. However, women loved him in different ways; he had charisma and charm; he had families and children and actors found him to be inspirational and nurturing. He was a generous and supportive director and fiercely protective of his films and the integrity that had got them made in the first place.

It is probably time that is the best judge of a work of art. How does it speak to us now, after all these years – when the circumstances of its production are largely unremembered and the human frailty of its creators (possibly something that may well have played a central role in the work’s creation in the first place) long-forgotten?

Nicholas Ray managed to direct, in spite of his flaws, several movies in which flawed people are represented, treated with respect but also have their failings writ large upon the big screen. His characters make mistakes, the wrong decisions and sometimes do great harm.

But for fleeting moments, they are loved and we, the audience can empathise with them.

This is one of film’s greatest achievements – it is an art form which (to quote Gregory Peck in To Kill a Mockingbird) allows us “to walk around in another man’s shoes” for a while.

Ray’s shoes may well be scuffed and uncomfortable; made of hard leather and a few sizes too big for us.

But that doesn’t mean to say that we shouldn’t try to wear them for 90 minutes or so. Indeed, for some of us, they may actually be quite a good fit.

Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar is showing on Saturday 22nd November (3.15pm). Click here to book tickets.

Dr Andrew C Webber is a Film teacher and examiner with 40 years’ experience. He contributed to both the sadly defunct Cinema of the 70s and 80s magazines (still available on Amazon); cassette gazette fanzine (available from cassette pirate on e-bay) and the Low Noise music podcast, available on Spotify and Apple podcasts (about to begin its fifth season). He also spoke at this year’s Vertigo 67 International Alfred Hitchcock conference at Trinity College in Dublin.