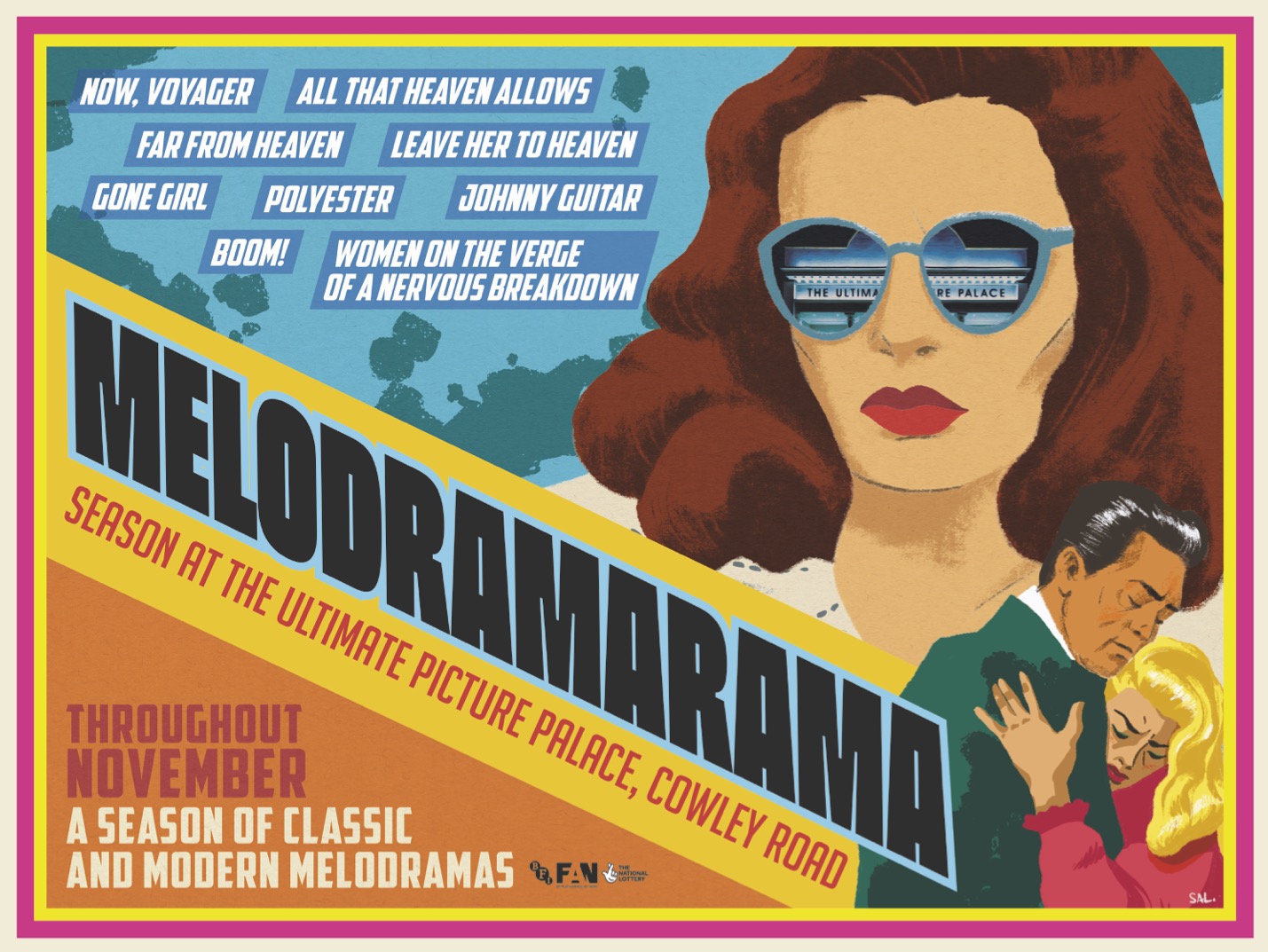

This piece is adapted from an introduction given live by Georgia Humphreys at our Melodramarama! season double-bill of Leave Her to Heaven and Gone Girl on Saturday 15th November 2025.

Throughout this November, we’ve been luxuriating in the many splendoured guises of melodrama, as we explore a selection of Golden Age Hollywood classics paired with the modern gems they’ve inspired. These films were chosen to exemplify the rich bounty of what melodrama can offer us – they span westerns, romance, noir, and comedies, they embrace a sensational excess of colour and emotion, and in their queer resonance they thrive in a transcendental terrain between the ridiculous and the sublime – or what melodrama king Douglas Sirk called the ‘dialectic between high art and trash’. Crucially they are all ‘women’s pictures’. In contrast to today’s Hollywood which is dominated by tentpole blockbusters designed to target one homogenised demographic for ‘all audiences’, the woman’s picture was a commercial cornerstone of Hollywood studio filmmaking, that took many forms from the silent era to the 70s, but found its peak in the 1940s and 50s. These films were made to appeal to women, focused on women’s narratives, and were the bread and butter of some of the most potent actresses of the age, offering them dynamic, complex roles that burnished their star power and versatility. These films chart the metamorphoses of women reckoning with desire and dignity, the chafing constraints of class and gender; women who confront scandal and defy decorum. It is only fitting then that in the most auspicious month of Noirvember, we find ourselves paying tribute to the wicked femme fatales of John M. Stahl’s Leave Her to Heaven, and David Fincher’s Gone Girl.

Noir only earned its popular moniker retrospectively – prior to 1946, these films were marketed as tough melodramas, whose heightened language evoked the American spirit corrupted by war, and the blossoming canker of cynicism and disillusionment that followed. These thrillers trafficked in lurid scenarios and criminal exploits, vicious characters, and a hardboiled realism made treacherous by the nightmare alleys and warped chiaroscuro of its trademark black and white photography. Arguably more mood than genre, the dark, protean expressions of noir are polymorphously perverse in both tone and form, epitomised in the notorious icon of the femme fatale. Beyond the stock image of perfidious dames and the suckers and swine they manage to ensorcel, the femme fatale endures and captivates because she is the primordial sire of the witch. In her book Caliban and the Witch, Silvia Federici isolates the birth of capitalism as inextricable from the persecution of women in the witch trials. The witch stood as a dark omen of woman outside the bondage of labour, free from the yoke of men, an incarnation of “all that capitalism had to destroy: the heretic, the healer, the disobedient wife”. Weird warlock Ray Bradbury once proclaimed that “a witch is born out of the true hungers of her time”, and so the femme fatale rises as a cunning, ravenous phoenix out of the furnace of wartime. Ill-content stoking the hearth, she instead skewers the archetypes of mother, maiden, crone, the stifling roles of housewife, ingenue, girl next door. She simmers with cruel mirth, survives on her wits, and pursues her delights with venal relish, wreaking havoc on the men who foolishly wander into her lair, entranced by her glamour. Magical historian Pam Grossman confirms the allure of the witch as “…arguably the only female archetype that has power on its own terms…she is not defined by anyone else. Wife, sister, mother, virgin, whore…the witch stands entirely on her own.” Calling upon her foremothers, the femme fatale offers her poisoned chalice to us, and we drink deep.

For decades, the murky shroud of noir totally eclipsed consideration of Leave Her to Heaven from within its deadly brood, but on its release in 1945 it newly anointed the femme fatale in gleaming technicolour. Director John M. Stahl was then known for his melodramatic oeuvre, including the original versions of A Magnificent Obsession and Imitation of Life, famously remade by Douglas Sirk in the 1950s. For many, Leave Her to Heaven’s perilous camouflage may have obscured its beating black heart, but its uncanny enchantment spawned Gillian Flynn’s novel and screenplay of Gone Girl. After backlash to the abject femininity of her novel Sharp Objects, Flynn wrote that she mourned “the lack of good, potent female villains…violent, wicked, scary women…women have spent so many years girl-powering ourselves — to the point of almost parodic encouragement — we’ve left no room to acknowledge our dark side. Dark sides are important. They should be nurtured like nasty black orchids.” The most magnificent black orchid of noir is found in Leave Her to Heaven’s Ellen Berent, played by Gene Tierney, a woman hell bent on possessing her husband to the ends of the earth. When she came to write Gone Girl, Gillian Flynn conjured the spirit of her “favourite femme noire of all time” in her creation of Amy Dunne, who is the neo-noir bad seed of Ellen; narcissistic, Machievellian, and deliciously psychotic. There is no Amazing Amy without Enchanting Ellen.

Ellen Berent is Gene Tierney’s most memorable role, a titanic performance of lustrous monstrosity and unbridled power that situates her as wretched Queen of the femme fatales, a blazing consummation of her mythic lineage from the witch. Cinematographer Leon Shamroy’s rich, oceanic palette evokes John William Waterhouse’s paintings of Circe, an elemental sorcery that renders fatalism with diabolical lushness and precision, to create a world in thrall to our lead actress, wrought in her bewitching blue-green eyes. Glamour in its arcane sense means spell, and the witch and the femme fatale ply the same sensual magicks; glamour is her arsenal, apothecary, and ruinous currency, channelled through clothing, makeup, and perfume. Ellen’s signature scent is patchouli, her husband’s eventual pet name for her. Makeup artist Ben Nye highlights her terrible and ethereal beauty with poison apple lips, her luminous skin and stormtide eyes forming an imperious, opaque mask. Ellen’s costumes were crafted by Tierney’s then husband, Oleg Cassini, a fashion designer who went on to create the signature look of Jackie Kennedy when she was First Lady. Ellen’s immaculate couture structurally channels her immaterial power; indeed every fibre of the film confirms her seemingly supernatural dominion. Oblique shadows of noir converge into a spider’s web cast against the interiors of her family ranch, into which wanders Richard the pitiful fly; the pagan bombast of Alfred Newman’s score announces that when we look upon Ellen, we look upon the same silhouette as Hippolyta, Medea, Lilith and Hecate.

Declared by Martin Scorsese as one of the “most underrated actresses of the Golden era”, Gene Tierney was an arresting shape shifter, a sphinx whose face was her most sublime instrument, wielding her beauty with supreme perception and suggestion. Darryl Zanuck, head of Twentieth Century Fox, was so beguiled by her transformation when he saw her in a Broadway production, that he tried to sign her twice in one night, not realising the stunning woman he’d spied on the dancefloor of The Stork Club was indeed the same woman he’d just seen on stage. Tierney had read Ben Ames Williams’s novel Leave Her to Heaven, and after learning Fox had bought the film rights, successfully campaigned to Zanuck for the part, later writing in her autobiography: “the role was a plum, the kind of character Bette Davis might have played, that of a bitchy woman…few actresses can resist playing bitchy women.” Tierney’s chilling visage imbues Ellen with a masculine zeal and indomitable will; but also a subversive sympathy, as her omnipotence starts to wilt under the claustrophobic veneers of wife and domestic goddess.

Long chastised as symbolic of the male gaze, and in each new iteration sparking backlash, the femme fatale sharply refracts male fear and desire of feminine power, but her transgressions are threshold to deeply cathartic pleasures, her savage pathology always standing as a black mirror of women’s current oppressions. Gone Girl is a nihilistic satire of heterosexual marriage as a twisted game of deception and role play, scintillating with David Fincher’s trademark perversity. Amy’s now immortal Cool Girl speech seethes against the toxic bubblegum misogyny of the early 2000s, an era of crude postfeminism that is now resurging with diet culture, incels and the manosphere, the trad wife, the revoking of Roe V Wade, and persecution of our trans sisters. Like Ellen, Amy scorns the banal trappings of domesticity, and finds new life in her deranged machinations. For her sangfroid blonde, Rosamund Pike drew upon the brazen balls of Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct, the searing intensity of Joan Crawford in Johnny Guitar, and the aloof, manicured poise of public figures like Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, wife of JFK Jr. Amy is shrewd to the bloodthirsty engine of the media and true crime, and violently weaponises the shrapnel of the fragile white woman in peril to achieve her ends.

Where Fincher delights in explicit carnage, Stahl and Tierney could only sabotage the boundaries of implied violence and taboo.The film was produced under the Hays/Production code, a self imposed censorship adopted by Hollywood from 1934 until the late 1960s, which heavily regulated what could and couldn’t be depicted on film, and insisted that any moral deviance shown on screen must be punished. To spite Hays’ hammer of the witches, Leave Her to Heaven manages to smuggle in some shockingly transgressive material for its time, and like Gone Girl, its leading lady never looks more obscenely radiant than when she is in the throes of a heinous act. The femme fatale has hexed a century of cinema, resurrected again and again in a perpetual season of the witch that is time without end, our Maleficent obsession. She has us in her grasp, and she’ll never let us go. Never, never, never.

Georgia Humphreys is a film writer and programmer, who has written for Indicator. She co-curated the UPP’s Melodramarama! classics series, produced in association with the BFI as part of their nationwide season, Too Much: Melodrama on Film. You can find her writing at lustyscripps.substack.com, or @lusty_scripps on Letterboxd.