Almost 50 years after its initial release, Francis Ford Coppola’s epic Vietnam war movie Apocalypse Now has lost none of its power – something you can judge for yourself when the “Final Cut” of the movie is screened at the UPP on Saturday 9th August.

It’s one of the few films I remember seeing in the late 70s that, as soon as it was over, I wanted to see it again (and did so a few days later). There was a lot to take in: an epic running time (153 minutes in 35 mm); Vittorio Storaro’s mesmerising cinematography; Walter Murch’s brilliant sound design; staggering performances from (amongst others) Martin Sheen, Marlon Brando, Dennis Hopper and Robert Duvall; that elliptical (at the time anti-climatic) ending; those literary references (Heart of Darkness and TS Eliot); the Playboy bunnies and Credence; The Doors’ This is the End as the first words we hear in the film; the Michael Herr scripted narration; the sheer, bloody, expensive madness of it all. Apocalypse Now appeared to have everything a movie needed to appeal to a disaffected, post punk audience of adolescent kids: hell, with a title like that, in an era of Thatcher and Reagan, how could it not?

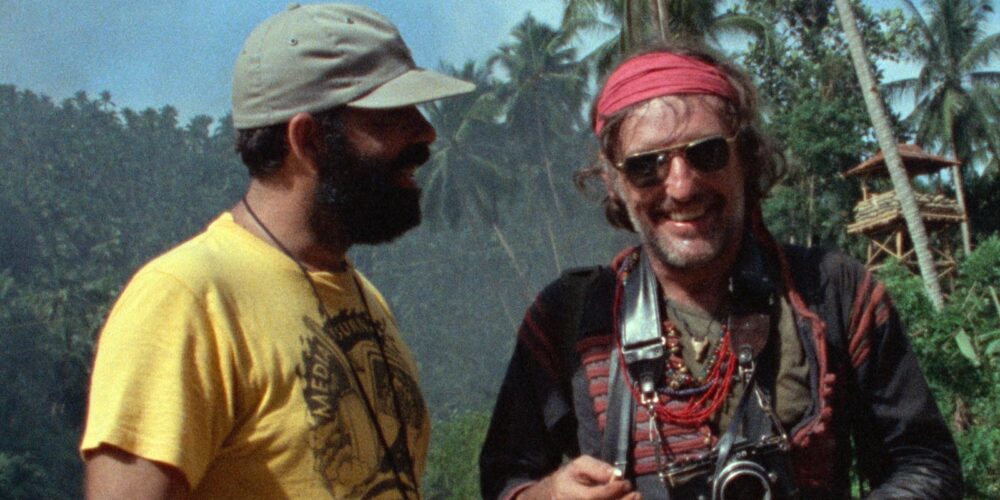

Of course, at the time, whilst some of the trials and tribulations behind the making of the film had been leaked out to the popular press, the production had none of the “legendary” qualities it has subsequently acquired and which were fuelled, in part, by Coppola’s wife Eleanor’s behind-the-scenes documentary about the making of the film Hearts of Darkness, which was released 12 years later (you can see this too at the UPP and it’s well worth checking out – arguably one of the greatest films about film making). What we didn’t realise at the time, however, was that this was also, somehow, the culmination of something special that had been taking place right under our noses and which we thought would never end – but New American cinema was reaching the end of its innings and Bazin and Sarris’ auteur theory, which had seemed so prescient then, was, in some ways, a significant player in its demise.

It would be fair to say that the first two Godfather films, which Coppola directed in the early 70s, are probably “better” than Apocalypse Now: tighter, more coherent, subtle. It would also be fair to say that, after Apocalypse Now, Coppola struggles to make anything in the same league (though that’s not to say he completely loses it: The Outsiders and Rumblefish are both refreshing antidotes to the excesses of Now and I have a soft spot for One from the Heart – his ambitious Tom Waits musical, which died a singular death at the box office in 1982, costing $26 million and recouping just over $600,000. Bram Stoker’s Dracula also has its admirers). But, in fact, it would probably be reasonable to suggest that 1996’s Jack, which starred Robin Williams, is up there with Woody Allen’s 2007 Cassandra’s Dream and Scorsese’s 2016 Silence as one of the worst films ever made by major American film director.

So what went wrong? Why might Apocalypse Now mark the beginning of the end? And why, somehow, “blame” Sarris et al.?

Rather like Hitchcock before him, I think it’s a case of hubris. When Truffaut interviewed Hitchcock at great length for his book about his entire body of work in 1962, he made a case for the master of suspense being, indeed, the master of every aspect of the movies he had directed. Hitchcock, now raised to the status of a great “artist,” goes on to direct a number of increasingly weak films – Torn Curtain, Topaz and Frenzy (which takes full advantage of the new X certificate and which reveals that he was far more effective when he suggested sex and violence rather that represented it explicitly). He also no longer collaborates with cinematographer Robert Burks (who died in 1968), editor George Tomasini (who had died in 1964), graphic designer Saul Bass (who lived on till 1996) and, most significantly, composer Bernard Herrmann, who was ignominiously “sacked” after scoring Torn Curtain and then had his soundtrack replaced by John (Tom Jones and, subsequently, A Bridge Too Far, amongst many others) Addison, leading to a complete breakdown in his relationship with Hitchcock with whom he, apparently, never spoke again.

OK, the times they were a-changing and Hitchcock was growing older and increasingly alcoholic, but you can’t help but imagine him thinking to himself that everything he touched turned to gold, regardless of whether it was actually any good or not and somehow this impaired his judgement, which had hitherto served him well when it came to his collaborations with both actors and those working behind the scenes.

Coppola does not have any similar “fallings out” with his team mates (both actor Frederick Forrest and cinematographer Storaro return for the One from the Heart debacle, for example) but, as Eleanor Coppola’s film reveals, he certainly saw himself as the artist responsible for Apocalypse Now during its production (and why shouldn’t he – he practically funded the entire thing himself, after all). But, it’s quite possible that when everyone around you is proclaiming that you are some sort of visionary genius that you soon begin to believe it. And maybe, in the end, money and commerce are never going to be easy bedfellows for a maverick genius (as Orson Welles had discovered, many years previously).

Michael Cimino, who had pipped Coppola to the post by releasing his epic ‘Nam movie The Deer Hunter in 1978, followed that Oscar winner with Heaven’s Gate, the notoriously expensive western in 1980 (cost $44 million – gross $3.5) which resulted in the end of United Artists, the studio responsible for funding it. I am glad that the critical drubbing the film received on its first release has been revised and the full length version restored – revealing that Heaven’s Gate may well be one of the greatest films of the decade, but the point is very similar. Here is a director, given the chance to indulge himself at the studio’s expense, turning out something that absolutely no one at the time had the vaguest interest in.

The point I’m making here is not that the best “auteur” directors are also the greatest collaborators (although, in truth they probably are). Nor that every expensive “flop” is somehow an unalloyed masterpiece (though a great many are – Once Upon a Time in America, for example). The thing I’m saying is that, for reasons which are too complicated to go into detail with here (the demise of the studio system; the new permissiveness; the birth of the “teenager;” LSD; the stratospheric success of Easy Rider [let us not forget that Hopper follows this one with his own incoherent and indulgent mess The Last Movie]; the impact of television; Civil Rights and Second Wave Feminism; the ageing process of the big stars; Vietnam, Watergate, Woodstock, Altamont; the Movie Brats and the birth of film as an academic study etc.) there was a halcyon period from the late 60s through to the early 1980s when Hollywood took huge risks and appeared to not to play it safe. But it was over too soon.

The decade gave us major films by new directors. who often crashed and burned in spectacular fashion but who also made some of the best acted, most thought provoking and daring films ever to be produced in the USA. It was a period when the medium of film went through significant technical and aesthetic upheavals and the doors to Hollywoodland were briefly opened (for a while) and through them charged the likes of Spielberg, Malick, Friedkin, De Palma, Scorsese, Altman, Oliver Stone, Allen, Romero, Cronenberg, Elaine May, Mike Nichols, Pollack, Milos Forman, Hal Ashby, Lumet, Penn and Kubrick, bringing with them talented new actors and technicians and making grown up films for adult audiences. Which made money – suggesting that audiences then were willing to lap up intelligent, thought-provoking and often ravishingly beautiful cinema – and that Hollywood was more than capable of catering to the demand.

That’s not to say there haven’t been great movies made in the last 30 years or that there are no interesting directors working in Hollywood anymore. Far from it. But the excitement and creativity of Hollywood in the 70s and a film like Apocalypse Now actually getting the green light and finding an audience is something that we can only, now, look back on with a sense of bemused wonderment.

It’s not a case of “they don’t make ‘em like that, anymore,” but rather “they once flocked to see stuff like that, you know” and wasn’t the world, somehow, a better place, when they did?

Dr Andrew C Webber is a Film teacher and examiner with 39 years’ experience. He currently contributes to both the Cinema of the 70s and 80s magazines (available on Amazon); cassette gazette fanzine (available from cassette pirate on e-bay) and the Low Noise music podcast available on Spotify and Apple podcasts.